|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

Africa/Global: Targeting Corporate Shell Games

AfricaFocus Bulletin

October 9, 2019 (2019-10-09)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

“Across the world, citizens who want their governments to implement

policies to reduce inequalities, address climate change and looming

ecological disaster, provide better public services and amenities,

ensure social protection, generate quality employment and so on,

are always confronted with one question: where is the money? We are

constantly told that governments cannot afford the necessary

expenditure; that running fiscal deficits will lead to financial

chaos and crisis; and that raising taxes will simply drive away

investment. But this is not just misleading; it is simply wrong.

Governments are constrained in their resources because they tolerate widespread tax evasion and avoidance. ” - Professor Jayati

Ghosh, Jawaharlal Nehru University

This AfricaFocus Bulletin contains excerpts from a new report from

Christian Aid and allied organizations, calling for a comprehensive

rights-based definition of illicit financial flows, including both

illegal tax evasion and abusive tax avoidance that uses biased laws

and gray-area loopholes to minimize the taxes paid by corporations

and the ultra-rich. The report provides a clear argument,

supplemented by case studies from Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

The excerpts below include cases of a Irish tax treaty with Ghana

and a major Canadian mining company in Zambia, documenting how

legal avenues are structured to deprive countries of needed

revenue.

This answer to “where is the money” for public needs applies

worldwide, but is particularly relevant on the African continent,

where tax revenues are the lowest and the needs are the greatest.

As the report notes, African civil society and inter-governmental

organizations such as the UN Economic Commission for Africa have

taken the lead on pressing this case in both national and

international arenas. This latest report is a marker of how the

common-sense answer is gaining ground internationally as well.

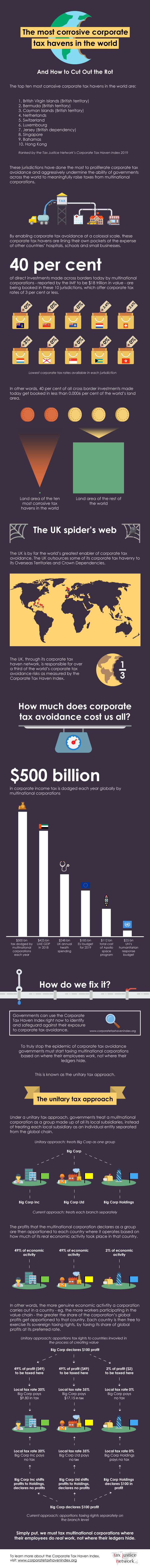

Also included in the AfricaFocus Bulletin is an extensive and well-

crafted infographic from the Tax Justice Network making the same

case.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on illicit financial flows,

visit

http://www.africafocus.org/intro-iff.php

For another recent commentary on the need for fundamental corporate

tax reform, see "No More Half Measures on Corporate

Taxes," by Joseph Stiglitz, in Commond Dreams, October 8,

2019..

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Trapped in Illicit Finance: How abusive tax and trade practices

harm human rights

September 2019

Christian Aid

[Excerpts only. For full text, including figures and footnotes,

visit

https://www.christianaid.org.uk/resources/about-us/trapped-illicit-finance-report]

Executive summary

On September 26, 2019, world leaders [gathered] at the UN General

Assembly (UNGA) in New York, for high-level talks on finance for

development. One burning question on the agenda is the financial

chasm facing the SDGs.

Adopted by the UNGA in 2015, the 17 goals offer a roadmap for

ending poverty, protecting the planet and ensuring prosperity for

all, by 2030. But with little over a decade to go, vast amounts of

public and private finance still need to be found if they are to be

realised within the timeframe. The funding gap for delivering the

goals from private sector sources alone is estimated at $2.5tn.

In this report, Christian Aid and our partners propose a simple

solution for plugging some of this funding gap: we must stop

tolerating the abusive, unethical, immoral illicit financial flows

(IFFs) that rob the poor to enrich the wealthy.

Our estimates show that IFFs cause tax losses of $416bn in the

global South. This is money that could enable governments to

deliver much-needed public services, and bring us closer to a world

where all experience dignity, equality and justice. As eminent

economist Professor Jayati Ghosh stated in the report foreword:

‘Illicit financial flows – both illegal and legal – may be the

major constraint to development and achieving human rights today’.

World leaders have previously committed to fight IFFs. At the Third

International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD) in

2015, participants agreed to ‘substantially reduce illicit

financial flows by 2030, with a view to eventually eliminating

them’. A similar commitment was made when the UN 2030 Agenda was

agreed.

However – and this is the crucial point – what has been missing

until now has been a robust definition of IFFs.

Governments of the global North insist on a legalistic definition

that would only capture flows of money universally accepted as

being illegal, eg, money laundering or corruption. However, we and

many of our partners in the global South believe what matters is

not whether flows of money or tax practices are legal, but whether

they are abusive, harmful or limit governments’ ability to deliver

on their human rights obligations. ...

That’s why Christian Aid is calling for the debate around IFFs to

shift towards a rights-based one. We want the definition of IFFs

broadened to refer to ‘cross-border flows of money that are either

illegal or abusive of laws in their origin, or during their

movement or use’. It is not about whether it’s illegal, but

immoral.

Christian Aid also believes the UN should establish structures to

define IFFs based on this rights-based definition. This would

require the UN to play a more prominent role in setting the rules

and conventions for taxing TNCs, and to expedite international tax

cooperation by establishing a UN tax body to decide on taxing

rules.

Addressing IFFs is not just about funding the SDGs – important as

this is. It is also about addressing the systemic issues that

continue to undermine poor countries’ abilities to raise revenue

and move beyond a reliance on aid. In that respect it is a stand-

alone process: one that is not just tied to the 2030 Agenda for

Sustainable Development, but which is grounded in justice and

equity.

Our estimates show that illicit financial flows strip poorer

nations of revenue losses to the tune of $416bn per year.

This is through practices including tax abuses and avoidance by

TNCs and wealthy individuals, and tax losses due to tax evasion

arising from companies who deliberately misprice goods and

commodities to minimise tax liability.

Introduction: Illicit financial flows are a violation of human

rights

An exact definition of IFFs has not been agreed internationally;

but for the purposes of this report, the term can be defined simply

as money that leaves countries where it should in fact be

contributing to development efforts and the achievement of human

rights. In other words, IFFs may be defined as ‘flows of money that

are either illegal or abusive of laws in their origin, or during

their movement or use’.

These include practices such as tax abuse, abusive tax incentives,

abusive use of bilateral and multilateral trade treaties, misuse of

double tax treaties, odious debt, abusive use of mutual arbitration

procedures, harmful tax practices, unjust investment agreements,

money laundering, trade mis-invoicing, abusive transfer pricing,

illicit money transfers, crime, bribery, the illicit drugs trade,

corruption and the ‘offshore’ trust industry.

The issue is ultimately about the power of who makes the rules and

norms in the global economy regarding these issues. For too long,

they have been decided in clubs of countries comprising mainly of,

or led by, the global North such as the G7 or the G20, or indeed

the OECD that does not take the legitimate interests of countries

in the global South adequately into consideration.

Tackling IFFs is not a new concern. For decades, the issue has been

discussed either as capital flight or in terms of tax avoidance;

and more recently, to understand the activities of

multinational enterprises,and in terms of wealth held

offshore. The novelty is grouping these practices

together within an internationally agreed definition of IFFs, along

with transnational crime and corrupt activities.

Combining these practices presents us with a fuller, more

frightening picture of how today’s global financial system is

centred on secrecy jurisdictions and corporate tax havens that

facilitate these activities, as well as corruption and

transnational organised crime. There is no way to achieve the

ambitious 2030 Agenda and the SDGs without stopping the bleeding of

hundreds of billions of dollars in IFFs.

The momentum for tackling IFFs is coming from governments, civil

society and regional bodies from the global South such as the

African Union that have long highlighted the damage caused by IFFs.

Notably, in 2015 a coalition of African organisations launched a

civil society campaign called Stop the Bleeding in a bid to

highlight the billions of dollars illicitly flowing out of Africa

each year. Many African governments, and the Group of

77 of countries in the global South in the UNGA, raise the issue of

IFFs in their interventions.

The 7th annual Pan Africa Conference on Illicit

Financial flows and Taxation, held in Nairobi on October 1-3, 2019,

sponsored by the Tax Justice Network-Africa and a wide range of

other civil society and inter-governmental institutions, focused on

the challenge of taxing digital enterprises, which require new

technologies to track and tax profits across borders.

If the definition of IFFs in the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs (an

initial draft definition is expected by the end of 2019) includes

only activities that are already illegal – such as corruption,

crime and tax evasion – there will be no mandate from the 2030

Agenda to tackle tax abuses that far outweigh these other

activities in terms of revenues lost from countries in the global

South. there is a risk that, under the guise of ‘licit’ financial

flows via tax havens, this will only exacerbate the problem.

…

Meanwhile, the secretariat of the UN Financing for Sustainable

Development Office has analysed the situation and concluded that

there is a ‘grey zone’ in which the dividing line between legal and

illegal financial flows is blurred due to a lack of resources, a

lack of access to data and discrepancies between how data are

reported to tax authorities, the media, and shareholders in private

databases.

In this report, we highlight what goes on in this grey zone and

propose the use of principles derived from international human

rights law to understand practices that constitute harmful

activities even though they may not be illegal in all jurisdictions

where a TNC has operations; where a transaction is taking place, in

terms of trade mispricing issues; or where wealth is held offshore.

The problem lies in the mismatches, misunderstandings and lack of

commonly agreed principles between the global North and the global

South in terms of international economic governance that give rise

to IFFs, as seen in Figure 1.

The definition of IFFs is being debated both within international

development frameworks and in human rights monitoring bodies. It is

an important definition, as it will determine the mandates at the

global level to monitor the financial system, national efforts to

combat IFFs in the Global South, and international development

cooperation as well as south-south cooperation. …

The first definition, which we call ‘legalistic’, is what is also

often described as a narrow definition of IFFs, used by a number of

international organisations, including the World Bank, the IMF, the

OECD and UNODC. The OECD refers to ‘a set of methods and practices

aimed at transferring financial capital out of a country in

contravention of national or international laws’.

The second definition is what we would call ‘normative’: it defines

IFFs in terms of a normative problem in how laws, rules and

regulations are actually established, rather than focusing merely

on the letter of the law. … What is considered

‘illegitimate’ is discussed through case study evidence and covers

practices such as corrupt government deals, tax abuse, abusive tax

incentives and other concerns that further expand the focus of the

discussion on IFFs.

The third definition builds on the first and second definitions, as

it tries to define a normative framework around what should be

considered ‘illegitimate’. …

This definition is supported mainly by UNCTAD, which has analysed

IFFs in terms of their economic and development losses. Under this

definition, UNCTAD considers that ‘the key criterion used is

whether such tax-motivated IFFs are justified from an economic

point of view’. If considerable tax losses are

associated with IFFs, UNCTAD considers that these serve to

undermine development outcomes that require greater fiscal

capabilities.

…

Finally, the fourth definition – as proposed by this report – also

builds on the first and second definitions, but views the issue

through a rights-based lens. The definition therefore includes all

aspects of tax abuse and tax avoidance, as these have a significant

impact on the availability of public resources for realising human

rights and upholding the rule of law. …

Source:

https://truthout.org/articles/we-could-eliminate-extreme-global-poverty-if-multinationals-paid-their-taxes/

[The remainder of the Christian Aid report includes a variety of

case studies, including in African countries. Excerpted below are

two cases, one in Ghana and the other in Zambia.]

Part one: Tax abuses by transnational corporations

TNCs are essentially companies that operate in multiple countries

and autonomous jurisdictions. As these countries and territories

have different (at times conflicting) tax and financial laws, the

international tax system is a patchwork with loopholes and

mismatches that companies (and the wealthy individuals who own

them) can exploit to pay less tax – either legally (albeit often

through abusive practices) or illegally, in the hope that they will

not get caught due to the high degree of secrecy and complexity

that characterises the international financial system.

A TNC is taxed separately for each of its legal entities in each

territory in which it operates. Thus, if a TNC has 200 different

subsidiaries and affiliates, each one of them must file its own tax

return. This separate treatment of the different legal entities of

TNCs is set out in the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines, even

though – for strategic purposes, and in the eyes of shareholders

who seek to profit from the activities of the entire group, rather

than those of its individual parts – the company is essentially a

single entity.These separate entities are assumed to be

trading at ‘arm’s length’ – that is, as if they were unrelated

parties – under the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines.

Meanwhile, human rights norms – such as the UN Guiding Principles

on Business and Human Rights and various laws on

mandatory human rights due diligence in Europe–

establish that companies should be treated as single entities in

light of their human rights obligations for their entire global

operations, including their supply chains. Corporate accountability

efforts also point in this direction, including the EU Non-

financial Reporting Directive, the US Dodd- Frank Act and the UK

Modern Slavery Act. The tax and human rights angle on treating

corporates as single strategic entities has thus far had little

impact on the cross-border tax treatment of TNCs; but it is logical

to treat companies as single taxable entities with respect to

international human rights norms.

TNCs – for good reason – pool some of their resources in shared

intra-group functions, such as financing, procurement, sales, human

resources, brands, patents and management services, which are held

in a specific subsidiary or subsidiaries and sold on to other

subsidiaries as corporate services. If these ‘transfer prices’ are

established at abusively low or high levels, they can be used for

‘profit shifting’, which often aims to reduce profits in high-tax

countries and jurisdictions and report profits from such collective

functions in low-tax countries and jurisdictions. TNCs may seek to

maximise their profits (often post-tax profits rather than pre-tax

profits) at a global level by routing trade, financing and

investment through countries and jurisdictions that present tax

advantages.

This type of behaviour is the focus of the OECD’s Base Erosion and

Profit Shifting (BEPS) project, which aimed to end such practices,

but has largely failed to do so due to a lack of agreement on how

to tax TNCs globally. At present, the UN only has an expert

committee on international tax matters, whose members are

restricted to commenting on such matters in their expert capacity

as individuals, rather than proposing plans for new rules and

regulations on the taxation of TNCs. Countries in the global South

have called for the establishment of a UN-based tax commission (or

a UN tax body) to negotiate how best to tax TNCs and improve

transparency and accountability in international tax matters.

The taxation of cross-border transactions such as interest,

royalty, dividend and other intra-firm payments is often governed

by double tax agreements (DTAs), such as the Ireland-Ghana DTA and

the Mauritius-India DTA discussed on the next few pages. The

applicable tax rates are often set at ever-lower levels in the hope

that this will increase investment, despite the lack of evidence to

support this view. …

Irish double tax agreement threatens revenue losses in Ghana

By Mike Lewis

This case study tells a political story rather than a technical

one. It shows how some governments are continuing to ignore new

international anti-avoidance standards, and the advice of their own

civil servants, in pursuing tax agreements that may create new

avenues for tax avoidance and deprive countries in the global South

of taxing rights.

DTAs can resolve tax dilemmas for companies and citizens living and

working between two countries, or investing in one country’s

economy from another. If they are incautiously or exploitatively

drafted, however, DTAs can unfairly deprive countries in the global

South of taxing rights that are vital to reduce aid dependency,

protect their citizens’ rights and develop their economies. They

can also open up new loopholes for profit shifting and other forms

of cross- border tax avoidance. In 2014, usually conservative IMF

tax policy staff advised that ‘developing countries...would be well

advised to sign treaties only with considerable caution’.

Ireland is expanding its network of DTAs. As this already

encompasses numerous agreements with developed economies, Ireland

is now particularly focused on signing new treaties with emerging

economies. Of eight treaties currently awaiting final signature

and/or ratification, five are with countries in the global South.

As part of its new Africa strategy launched in 2011,

Ireland targeted four emerging African economies for new DTAs,

including Ghana.

Ghana is the lowest-income of Ireland’s current prospective DTA

partners. A booming middle-income economy, it is also a vulnerable

one which is still a (small) recipient of Irish aid.

Over one in 20 Ghanaian children still die before their fifth

birthday; and despite major improvements, almost 4 million Ghanaian

children still live below the poverty line.Ghana’s tax

revenues also remain vulnerable: Ghana collects only around 16% of

its GDP in tax revenues, compared to 25-30% for most European

economies.

Although, from Ireland’s perspective, Ghana may be a relatively

small investment and trading partner, the new Ireland-Ghana DTA

matters greatly to Ghana, because according to Ghanaian statistics,

since 2012 Ireland has become Ghana’s largest source of FDI. By

2016 (the most recent year for which Ghanaian-reported FDI data are

available), Irish FDI constituted one-third of Ghana’s entire

reported FDI stock.Limiting Ghana’s taxing rights over

income, profits and economic activity between Ireland and Ghana may

thus have a significant impact on Ghanaian tax revenues.

Both parties signed the DTA in February 2018. Although approved by

Ireland’s Parliament in October 2018, it still requires approval

and ratification by the Ghanaian Parliament, meaning that the DTA’s

entry into force now rests on whether Ghanaian institutions find it

abusive or harmful, and request further changes to the treaty.

Imbalances of the Ghana-Ireland DTA

* The DTA will cut Ghanaian withholding tax on royalties to Ireland

from the domestic 15% rate to 8%, and on (closely related)

technical services fees from 20% to 10%. …

* The DTA will deny Ghana the right to tax capital gains from the

sale of assets in its territory (other than immovable property), if

the sale is executed through the offshore sale of shares in an

Irish holding company. This contradicts the recommendations of both

the IMF and the UN Tax Committee.Since Ireland appears,

according to Ghanaian statistics, to be the largest single source

of direct investment in Ghana’s economy, this provision could

potentially deprive Ghana of very large tax revenues when valuable

Ghanaian assets change hands.

* The DTA lacks any of the anti-avoidance provisions which OECD

member states, including Ireland, agreed in 2015 were necessary to

provide ‘the minimum level of protection against treaty abuse’. It

is therefore fully non-compliant with the OECD’s BEPS project

against tax avoidance and profit shifting, which Ireland has

repeatedly pledged to implement in full. ...

These features arguably contradict the Irish government’s own

commitments in Ireland’s international tax strategy: to support

‘improvements in domestic resource mobilisation [tax revenues] in

partner [developing] countries’, including through Ireland’s own

domestic tax policies;and to fully implement the OECD’s

BEPS project to prevent corporate tax avoidance.

…

Part two: Lost tax due to trade mispricing and trade mis-invoicing

International trade is not what it seems. Trade mispricing has

become a multibillion-dollar industry, in which trade handling

companies identify the least costly way to make a paper trail of

payments for goods, which often has nothing to do with their

physical movement. Unrelated importers and exporters utilise

offshore tax havens to route trade on paper to reduce the taxes

paid on border transactions, as they provide secrecy for practices

such as double invoicing and mis-invoicing – sub-categories of the

umbrella term ‘trade mispricing’.

When we talk about imports and exports, many think that goods flow

from one country to another relatively directly; and this is what

is shown in the international trade data maintained by the UN

Comtrade database and the IMF’s Direction of Trade Statistics

(DOTS). There are some legitimate discrepancies in the import value

reported for the same set of imports in the receiving country and

the export value in the exporting country that relate to shipments

via transit countries, regarding how goods are declared in value

(‘Free on Board’ is often used, but not by all countries).

The volumes of potential trade mispricing are absolutely eye-

watering. A representative sample of 30 African countries from 1970

to 2015 revealed that these countries lost a combined $1.4tn

through capital flight over the 46-year period; including interest

earnings lost on capital flight brought the cumulative amount to

$1.8tn.The average outflow from Africa for the years

2010 to 15 was estimated at $63bn under this methodology, lost

mainly from oil-rich African nations. …

The best estimates of tax losses due to trade mispricing come from

GFI, which has estimated that trade mispricing (encompassing both

illicit outflows and illicit inflows) in 2015 caused losses of

$940bn, based on the UN Comtrade data, while higher IMF DOTS would

show a loss of $1,690bn.Both of these figures, attempt

to estimate mismatches between the declared import price and the

export price in the same pair of countries or vice versa.

…

Zambia’s copper sector mispricing abuses

By Prof Attiya Waris

First Quantum Minerals (FQM) is Zambia’s largest mining company and

largest single taxpayer, and has been lauded as contributing more

than one-third of the Zambian government’s income.The

2015/2016 Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI) data

reveals that the Kansanshi mine provided 22% of tax revenue, while

7% was provided by another subsidiary. The main types of taxes that

FQM pays in Zambia are mineral royalties, followed by other types

of taxes. It is evident that the collection of mineral royalties is

relatively simple; the debate thus centres on the declaration of

correct production volumes and payments to governments, including

in EITI reporting.

Kansanshi Mining PLC, a subsidiary of Canadian mining and metals company First Quantum Minerals Ltd. (FQM)

FQM is listed on both the Toronto Stock Exchange and the London

Stock Exchange, and operates mining projects globally. It has a

number of local affiliates in Zambia, all with separate accounts.

The available data reveals discrepancies between the information

regarding FQM registered with the Zambian companies registry and

that held in the Orbis database. For instance, while cover

investments is shown to have been incorporated in Zambia in one

database search for FQM and Operations Ltd, in the Orbis database

there is no record of cover investments.

The Zambian Revenue Authority is reportedly accessing information

from Orbis and other proprietary company information databases in

order to improve its audits.The FQM data sheet, on the

other hand, indicates that the company is incorporated in Ireland.

These discrepancies make tax audits and tax assessments more

difficult in the absence of full country-by-country reporting under

the OECD initiative, due to the lack of information exchange with

other revenue authorities. The quickest way to facilitate full

country-by-country reporting would be to make the filings mandated

by the OECD public and available to all, including the revenue

authorities of countries in the global South.

FQM and its subsidiaries in Zambia are subject to various taxes,

from employee income taxes to VAT, mineral royalties and corporate

taxes, among others. However, the EITI disclosure for the year 2016

is not sub-divided by the types of taxes paid, so sensitive tax

information – such as corporate income tax payments per country of

operation – is unavailable.From the corporate structure

of FQM, depicted in Figure 8, we can see that its Zambian

operations involve offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands

(BVI) and Ireland.

The current lack of transparency affords abundant opportunities for

transfer pricing abuses. According to a claim before the Lusaka

High Court, between 2007 and 2014, FQM directors ordered over

$2.3bn of Kansanshi profits to be borrowed to FQM Finance Limited,

which performs treasury functions for the group.FQM

Finance then alledgedly started investing these funds from the

Kansanshi mine to grow the group without the consent of the

government- owned local minority shareholder, ZCCM-IH. According to

sources close to ZCCM-IH, its claim includes $228m in interest on

the $2.3bn, as well as a further 20% of the principal amount

($570m). FQM and the Kansanshi Mining PLC state that

they are firmly of the view that the allegations are untrue.

The proceedings are still underway in the Lusaka High Court

as of August 2019.

...

[another case] involving FQM was revealed in March 2018, when FQM

received an $8bn charge relating to unpaid import duties arising

from misdeclarations.The assessment concerned the

under-declaration and non-declaration of import duties on capital

items, consumables and spare parts for use at the Sentinel mine

from January 2013 to December 2017.Following a five-

year tax investigation, the losses were calculated at $540m, which

was found to amount to smuggling in the form of misdeclared customs

duties. In the case of smuggling charges, criminal fines may be

imposed.

The fine sought to be imposed on FQM has been duly calculated at

$2.1bn, as smuggling is punishable by a threefold fine in addition

to the assessed amount, with a further late payment charge of

$5.7bn, according to the company’s own disclosure. FQM refuted the

assessment. In July 2019 a settlement was reached for an

undisclosed amount.…

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. For a full archive and other resources,

see http://www.africafocus.org

|