|

Get AfricaFocus Bulletin by e-mail!

Format for print or mobile

India/Africa: Common Threads of Kanga and Vitenge

AfricaFocus Bulletin

September 14, 2020 (2020-09-14)

(Reposted from sources cited below)

Editor's Note

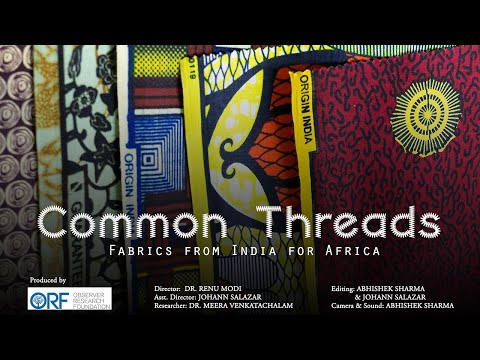

The new book Common Threads (along with an accompanying video, both

open access), explores the ties that bind India and Africa through

the material medium of cloth, from antiquity to the present. Cloth

made in India has been sold across African markets for millennia,

by Indian, African, and European traders. ... Most significantly,

it highlights the role of African consumers in defining the

evolution of these genres of fabric, and the centrality of people-to-people connections in sustaining the continued cosmopolitanism

of these transoceanic connectivities.

This AfricaFocus Bulletin features an interview with one of the

editors of this vividly illustrated book, brief excerpts from the

book, and a link to the 22-minute video which vividly portrays the

fabric and the people who make it, trade it, and wear it. For

anyone interested in the long history and present reality of South-

South cooperation across the Indian Ocean, this is an incredible

resource.

AfricaFocus normally focuses on current realities and crises. But

it is well worth making an occasional exception, even in terms of

understanding the present, because the world´s response to African

crises is still beset by cultural stereotypes and misunderstandings

deeply rooted in history. I highly recommend this well-researched

and well-presented project.

For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on culture, visit

http://www.africafocus.org/cultexp.php. For previous AfricaFocus Bulletins on trade, visit http://www.africafocus.org/tradexp.php.

The book Common Threads is available as a PDF download at https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/120547. A print version is available for order at

http://www.ascwebshop.nl/Common-threads-:-fabrics-made-in-India-for-Africa

The video is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jplcCfOfi5A.

++++++++++++++++++++++end editor's note+++++++++++++++++

|

Common threads – the ties that bind India and Africa through fabric

Cliffordene Norton, Meera Venkatachalam

Voertaal Academisch

2020-08-19

https://voertaal.nu/common-threads-the-ties-that-bind-india-and-africa-through-fabric/

Common threads: Fabrics made-in-India for Africa

Edited by M Venkatachalam, R Modi and J Salazar

Published by African Studies Centre Leiden

Common Threads explores the ties that bind India and Africa through

the material medium of cloth, from antiquity to the present. Cloth

made in India has been sold across African markets for millennia,

by Indian, African, and European traders. The history of this trade

offers perspectives into the rich stories of bi-directorial

migrations of peoples, across the Indian Ocean, the exchange of

visual aesthetics, and the co-production of cultures in the two

geographies. Common Threads uses photographs to tell the story of

the creation of these textiles in India, which today is

concentrated in the small town of Jetpur in the Rajkot district of

Cujarat. It sheds light on the artists and the agencies in India

that are involved in the design, production, and logistics of this

enterprise. Most significantly, it highlights the role of African

consumers in defining the evolution of these genres of fabric, and

the centrality of people-to-people connections in sustaining the

continued cosmopolitanism of these transoceanic connectivities.

|

|

|

Photo credits for vitenge on left and kanga on right:

http://pixabay.com and http://youtube.com.

Cliffordene Norton interviews Meera Venkatachalam, co-editor of

Common threads: Fabrics made-in-India for Africa.

Q: Congratulations on the publication of your book, Common threads:

Fabrics made-in-India for Africa. What was the inspiration behind

this book?

A: This project began when we learned that African prints were

being made in factories around Mumbai for consumers all over

Africa, from Nairobi to Lomé. We were well aware that African

prints were manufactured in the Netherlands and, more recently, in

China, but we did not know that the iconic wax print – among other

types of cloth – was being designed and manufactured in India. So,

we attempted to tell this story, contextualising India’s current

role in producing cloth for Africa against the backdrop of its

historical status as a major global cloth producer.

Q: Why focus on this history of the textile trade?

A: It is well known that India was a major producer of cloth for

millennia. But it is generally believed in India that the colonial

era disrupted Indian cloth production – that raw materials were

exported from India to Europe, and that British-manufactured goods

were received into the Indian market. However, a glimpse into the

textile trade between India and Africa in the colonial era reveals

that the textile industry – especially in western India and Mumbai

(then Bombay) – grew substantially in the colonial era by adapting

to the demand for cloth in Africa. This phenomenon fuelled colonial

Bombay’s industrialisation, a little-known historical fact.

Q: When did the textile trade between India and Africa start?

A: This trade is over 2 000 years old!

Q: The spice route between India and Africa is well known. Has your

research revealed any similarities or differences between these two

trade routes/products?

A: We have attempted to historicise our work and to view current

textile production in India for Africa against broader temporal

trajectories. There are both continuities and discontinuities.

The current trade to East Africa may be viewed as a continuity of

older precolonial and colonial routes and processes, which

facilitated the circulation of peoples, goods and capital between

India and East Africa. For instance, Indian families with strong

links to the Indian diaspora in East Africa are engaged in the

cloth trade today, relying on the know-how of Indians settled

there, for conducting market research and negotiating access to

markets. But today, we also find Indian traders operating in

markets in West Africa – this is a new phenomenon, as, unlike in

East Africa, Indian traders have never been present in West Africa

in large numbers until now.

Q: Common threads uses photographs to tell the story of the

creation of these textiles in India. Why did you use this research

method?

A: The patterns and designs represented in this cloth – from the

East African kanga to what is known as kitenge – tell stories that

are deeply embedded in the sociocultural matrixes of the people who

wear them in Africa. We wanted to show as many of them as possible

in our book.

Q: Take us through the process of compiling and editing the book.

A: It has taken us three and a half years to put this together. We

had to sift through large quantities of field notes, photographs

and video clips generated out of our fieldwork. We also read

previously published literature on the subject. Eventually, we

began to see it fall into place, and our focus came to rest on

Indian designers and merchants in the cloth trade, on the genres of

African designs and on the process of production in India.

Q: What did you edit out of this book?

A: As we began writing, we realised that we were telling the story

not just of the cloth trade between India and Africa, but of other

movements which were intertwined with the cloth trade – such as the

slave trade from Africa to India, and free and unfree migrations of

people from the Indian subcontinent to Africa. We tried to

incorporate as many of these related phenomena as possible, while

staying focused on cloth. Therefore, some of these themes are

introduced very briefly, and many details which we would have liked

to include are left out.

We also have a number of pictures of beautifully designed African wax prints and kangas which did not make it into the book!

Q: How would you bridge the gap from your research to research users?

A: We have tried to use as many visual aids as possible to achieve this, from the use of photographs to making a film.

Q: How do you see this book impacting the field?

A: We hope to highlight the current Indian agency in producing

cloth for Africa, which is not well known. We also hope to

highlight other themes in the study of India-Africa relations and

African studies, which are discussed only in passing in this book,

but are in need of more research. For instance, thousands of

itinerant African traders and entrepreneurs come to India several

times a year to buy consumer goods for sale in their countries of

origin. Also, India is home to a small but growing African diaspora

now – and very little is known about this.

Q: How do you feel about converting your research into the documentary Common threads – Fabrics from India for Africa?

Our film, also called Common threads: Fabrics made-in-India for Africa, was premiered at the Zanzibar International Film Festival in 2018 (ZIFF 2018) and was shortlisted in the documentaries section. It can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jplcCfOfi5A

We made the film in order to reach a broader non-academic audience,

and we hope this has been the case! We thank our publishers, ASCL,

for working with us to produce the book, and we are pleased that it

is open access.

******************************************************

Brief excerpts from Common Threads

The history of trade between India and Africa has been inextricably

linked through the material medium of textiles. ‘Common Threads:

Fabrics made in-India for Africa’, contextualises India’s role in

the production of textiles and the lesser-known trade in

beautifully printed cloth for African markets. This trade that has

existed since antiquity and continues to the present time has

created longstanding people-to-people connections across the Indian

Ocean. It showcases the way in which the production, trading, and

exchange of textiles manufactured in India has been governed by

discerning consumer preferences on the African continent for

centuries.

This project was conceptualised at the Centre for African Studies,

University of Mumbai, in early 2016. We learnt that there were

factories in western India – in Tarapur, on the outskirts of

Mumbai, and in the town of Jetpur, in Gujarat – that produce bright

and vibrant kanga and vitenge, ‘African prints’ for consumers

across Africa. This project entailed fieldwork mainly in Tarapur

(Maharashtra, India) and Jetpur (Gujarat, India), Nairobi and

Mombasa (Kenya), and Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar (Tanzania). The

project took about three years to complete. It culminated in this

photo-essay book and a documentary film.

There exists a commendable body of scholarly work on the subject,

published by established historians of textiles and the Indian

Ocean world, and by art historians. We read their work with great

interest, built upon the existing knowledge, and added an ‘India

focus’, to fill in the gap. We realised that rich oral narratives

of the ‘old diaspora’, mainly Gujaratis who had immigrated to East

Africa in the early nineteenth century and thereafter were not

documented although they had been a part of the designing, trading,

and consumption of these African prints – kanga and kitenge – since

the inception of these genres of cloth.

At ‘Mali Ya Abdulla’ (est.1887, Biashara Street, Mombasa), we were

privy to some of the most astounding printed fabrics, from the

colonial period or thereabouts. We have captured these on camera

and have showcased them in this volume. We also came across several

other noteworthy visual representations on cloth, which have deep

social, political, and cultural meanings to people in Africa. Thus,

each image printed on the fabric in this volume is a repository of

multiple aspects of life on the Swahili coast and beyond. The

textiles are also testimony to the transoceanic co-production of

cultures and cosmopolitanism of the Indian Ocean world. One example

is the little studied exchange of aesthetics of personal adornment,

family memories, and storytelling as described by writer Sultan

Somjee in his novel Home Between Crossings.

...

A kanga is a cloth with a thick border on all four sides, measuring

66 x 44 inches, worn in pairs around the waist and chest. Swahili

or English proverbs are often imprinted upon the kangas. In Jetpur,

kitenge refers to any nonkanga type of continuous fabric: 6 or 12

yards, printed in a variety of styles ranging from ‘wax prints’ to

batiks with a thin border. Vitenge are worn in a number of ways in

different cultural zones. Rural West African women wear two six-

yard pieces, one secured around the waist and another below the

shoulders, tied with a cord. The pieces do not necessarily

correspond to each other. Urban African women sew them into one or

two-piece dresses of different patterns, sometimes worn with

matching headgear. This two-piece dress, styled in the fashion of a

Victorian woman’s attire, is known as the kaba in Ghana, and a buba

and iro in the Yoruba-speaking belt of Nigeria. Varieties of

vitenge are also in demand in East African markets. The development

of East and West Africa as discrete cloth zones is a residual

feature of a longer history of India’s positioning within global

dynamics of trade.

...

Over the centuries, the Indian cloth trade has developed through

two very different trajectories across East and West Africa.

Geographically, East Africa is closer and therefore more accessible

from India. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (hereinafter ‘The

Periplus’), a Greco-Roman manual on trade and navigation from the

first century AD, describes an active trade between ports such as

Barygaza (Baruch) on the western coast of India and the East

African port cities such as Adulis of the Aksum Empire

(contemporary Eritrea), Malao in Berbera (contemporary Somalia),

and Rhapta in Azania (around present-day Dar es Salaam) (Schoff,

1912, pp. 22-3, 25-6; 28, 39). Facilitated by the monsoon winds,

the dhows (wooden 29boats with sails), moved peoples, goods, and

ideas between the coast of East Africa, and the shorelines of

western India and Arabia (Sherriff, 1987, p. 2).

This trade continued through the medieval period and received an

immense stimulus through the European presence in the Indian Ocean

during the colonial era. People, cultures, and ideologies of both

the terrains – India and Africa – were in frequent contact with

each other for centuries. Africans, generically known as Habshis (a

corruption of Habesha, the name used for Abyssinia or Ethiopia)

were frequently encountered in medieval and early- modern India.

They came as traders, soldiers, and slaves. Africans played a

crucial role in the history of Delhi, the Sultanates of Gujarat,

the pre-Maratha Deccan and the Bahmani kingdom (Alpers 2017, pp.

62-3).

Trade between India and West Africa followed a different

trajectory. Historically, Indian traders had little knowledge,

contact, or control over West African markets. This region was

located further away – double the distance as compared to East

Africa, which was only about 4000 kms away from Mumbai. In the pre-

colonial era, India simply did not have the same immediacy in West

African imagination as it did in East Africa, remaining a distant

construct, created through the re-envisioning of several cultural

interlocutors. Indian cloth entered West African markets as re-

exports as Indian cloth enjoyed a global reputation on account of

its high quality, variety, and colours. It was sold by

intermediaries – Arabs, Ottomans, other Africans, and Europeans –

through land routes from the Middle East, southern Europe, and the

Sahara. During the colonial era, Indian cotton continued to enter

West African markets through oceanic routes opened up by the

European colonial powers (Johnson, 1974; Lemire & Riello, 2006;

Riello, 2010).

...

People-to-people narratives in Indo-African relations

Popular accounts of the relations between the people of India and

countries in Africa are often marked by incidents of mutual

hostility. Africans of Indian origin have faced antagonism in their

adopted homes, culminating in the 1972 expulsion of Asians under

Idi Amin, whose reasons for expulsion were among other things,

driven by his ‘Africanisation’ agenda (Amor, 2003). Similarly,

Africans in India have been at the receiving end of sporadic but

consistent racist violence (Modi & D’Silva, 2016). In recent years,

even the symbolism of Gandhi, once seen as a bridge between India

and Africa because his struggle against imperialism was shaped by

his experiences in both regions, has become steeped in controversy

amid accusations of him being racist towards Black Africans.

However, these sensational incidents of antagonism, which have come

to occupy primacy in the narrative of Indo-African relations,

obfuscate a long, quotidian and an extraordinary history of

people-to-people connections that, on closer investigation, paints

a picture of co-existence and harmony. Many Indians in Africa are

thoroughly interwoven into the fabric of their adopted homelands

(Oonk, 2013). They prefer to be identified as Africans first and

foremost, and recognise themselves as ‘People of Indian Origin’

only secondarily (McCann, 2011). Similarly, many Africans are

integrated into the socio-cultural matrixes of their Indian host

communities, through community organisations and religious

networks, and play significant and valued roles in promoting inter-

cultural understanding. This complex dynamic of Indo-African

people-to-people relations in both geographies remains

understudied. This book is an evidence-based endeavor to shed light

on these long-standing associations and demonstrate that they

persevere to this day.

AfricaFocus Bulletin is an independent electronic publication

providing reposted commentary and analysis on African issues, with

a particular focus on U.S. and international policies. AfricaFocus

Bulletin is edited by William Minter. For an archive of previous Bulletins,

see http://www.africafocus.org,

Current links to books on AfricaFocus go to the non-profit bookshop.org, which supports independent bookshores and also provides commissions to affiliates such as AfricaFocus.

AfricaFocus Bulletin can be reached at africafocus@igc.org. Please

write to this address to suggest material for inclusion. For more

information about reposted material, please contact directly the

original source mentioned. To subscribe to receive future bulletins by email,

click here.

|